Small Wonders

story by Julia Steele

photos by Brian Suda

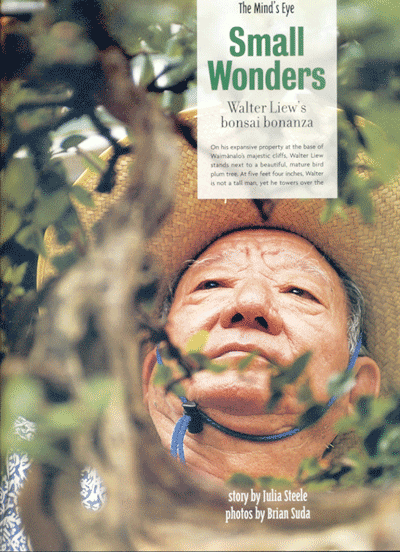

On his expansive property at the base of Waimanalo’s majestic cliffs, Walter Liew stands next to a beautiful, mature bird plum tree. At five feet four inches, Walter is not a tall man, yet he towers over the Lilliputian bonsai tree, which is eighteen inches high. The forty-five-year-old tree’s body—twined, full, solid—matches Walter’s own. Both man and tree are living proof that stature is not born of height alone.

"This tree is like my life," says Walter, continuing the thought. "Born in China, went to Taiwan. It went through drought, flood, lightning. It’s still very strong, after everything." As he speaks, Walter’s body seems filled with energy, spirit—what he would call chi.

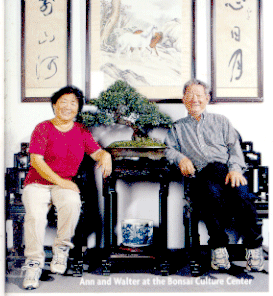

At sixty-nine, Walter has been a bonsai aficionado for over fifty years, since he was a young college student in Taiwan, and today he is a maestro of the craft. Three years ago, he created the Hawaii Bonsai Culture Center, "a museum of living art" featuring several hundred carefully shaped and miniaturized trees. When I drive out to meet him, he greets me at the center with a big smile and a warm handshake, then leads me into his large warehouse/office/antique depot and sits me down at an exquisite black-wood table underneath a massive purple lantern with gold tassels. In a former life, Walter was an antique dealer, and traces of that life remain: When I remark upon a particularly beautiful panel carving in the warehouse, he says: "This was the back of a settee at the Summer Palace near Manchuria. Emperor Shang-Feng and his two wives used to sit on it there. The settee wound up with General MacArthur in Japan. I bought the back part of it at an auction; the seat part went to William Randolph Hearst, who put it in the Hearst Castle. He turned it into a table and drank his coffee at it each Saturday morning." Walter is enthusiastic, funny and eager to tell me all about the amazing art of bonsai. "It heals mental stress," he says at the beginning of our conversation. "It’s therapeutic. Do you know the poem by Keats, ‘a thing of beauty is a joy forever’? This is extremely true of bonsai. It is a living art, an unfinished art. Bonsai can go on forever. |

|

"‘Bon’ means pot in Mandarin," Walter explains, "and ‘sai’ means plant, so ‘bonsai’ means, literally, a plant in a pot." He is determined to set the historical record straight: Contrary to popular belief, bonsai did not originate in Japan; rather, it was taken there by Buddhist monks from China in the thirteenth century. The art, he tells me, was started some 1,600 years earlier, during the Han dynasty, by Chinese physicians who traveled to the mountains in search of healing trees and herbs: "Soon they said, ‘I don’t want to travel so much, I want the herb nearer,’ so they took cuttings and grew the plants in pots. Gradually, artists in China began to reform the trees by cutting, pruning, trimming and using wire to produce styles that delighted them."

While the Japanese may not have invented bonsai, they did perpetuate the art. And it was a Japanese company, says Walter, that introduced bonsai to the Western world at a trade fair in Paris in 1898. Then, when large numbers of Japanese emigrated in the wake of World War II, they took the passion for bonsai with them around the world. And, later, it was in the overheated Japanese economy of the 1980s that the record price for a bonsai tree was paid: a cool $3 million for a black pine, purchased by Sony.

|

Liew was born in China, in the same town as Confucius, and grew up during the Japanese occupation. When he was twelve, he left for Taiwan with his family; there, he planned to be a mathematician, manipulating numbers instead of trees. But after completing a master’s in math, he stopped his studies and turned to bonsai instead. "I learned the art of bonsai in college," he tells me, "and I have loved it ever since. No matter where I go, I make friends through bonsai. I’m much happier this way than if I had stayed with math." By his own estimate, Walter devotes fourteen hours a day to his trees. He now has close to 300 on display at the center, is preparing another 400 to be "the elite of bonsai" in the near future, and is cultivating 5,000 "pre-bonsai" trees in his nursery. There are many good trees for creating bonsai, Walter says. Among the best are black pine, juniper, elm, the foo-kian tea tree, ficus, crepe myrtle and an elm from Russia called zelkovo. Walter begins shaping his trees when they’re about a year old ("the younger, the better," he says); to pick them, he looks to the trunk: If it’s strong and interesting, the tree is a good candidate for bonsai. "What makes them work," he says, "is if their trunks and branches can be bent and curved with wire to form a style." He wires the trunk and then, a year later, wires it again, and, a year later, again. He repeats the process until, by the time the tree is four or five years old, it is beginning to become a true bonsai. |

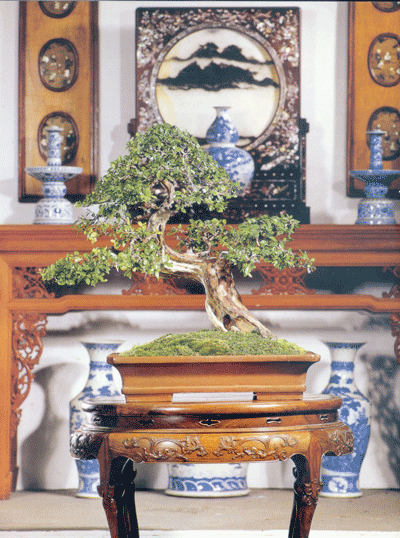

Walter rises from the table and invites me to see his trees. We walk out onto his lush, sixteen-acre property, which backs onto the Waimanalo cliffs. In the distance sits the small house where Walter lives with his wife, Ann; along the road sit hundreds of exquisite ceramic pots, which he imports from China. The first bonsai we examine is a delicately proportioned ironwood in a beautiful green pot. It is growing in a classic "informal upright style," in which the trunk is curved and tapering, and the branches alternate from side to side—a style that Walter tells me represents stability, gracefulness and firmness in life. "This tree is 110 years old," he says. "I’ve had it for the last thirty."

Next we look at an eighty-five-year-old Chinese banyan, or ficus tree. Its intricate root system clasps a large rock to create a stunning natural sculpture. As we tour the garden, Walter stops at each of his creations, occasionally pulling off a small branch or a few weeds taking residence in a pot. He approaches each tree with affection, and it’s clear he knows them all intimately. We see a small cypress tree with trunk and branches tightly wired; a bougainvillea whose lithe trunk looks almost human, like a dancer in a graceful pose; a fifty-five-year-old zelkovo; and a matched pair of elms. The evidence of Walter’s skill is everywhere. He shows me a cypress growing in a "cascade" style designed to mimic a tree that grows over water or near a cliff face. The tiny cypress juts out at an angle, as if it has been battered by high winds for years. Walter has used lime sulfur to kill part of its trunk, creating the effect that it has been hit by lightning. There is a delicate crepe myrtle, a perfectly miniaturized juniper tree, an ethereal foo-kian tea tree balancing on spaghetti-like roots and a lantana with a trunk shaped like a dragon. "Lots of people bring me their bonsai trees to improve," Walter says. "To them, the tree is just a plant in a pot. They’ve never wired it, never trained it. The shape and character of a bonsai reflect the love and care of the owner." |

|

|

The Bonsai Center is open to the public by appointment only, and Walter and Ann sell bonsai-ready seedlings from their nursery. For beginners, Walter offers a nine-week workshop at the center four times a year, where participants learn to shape their own trees. "You must always look for a good root system," he advises. "It is a good foundation for building." Other advice: "Cut the top of the tree, and the energy will be retained in the belly—the trunk and the roots."Finally, we come to the bird plum tree that has suffered so much: drought, flood, lightning. It is a lovely tree, healthy and vital like the man who has cared for it. Standing together, the man and the tree seem to offer another truth, one that is central to bonsai: that hardship in youth can mold the earth’s creatures into wondrous living things. Hawaii Bonsai Culture Center |

Page last updated: November 30, 2008 | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use